D.H. Lawrence

At first glance, slavery rhymes with the horrors of the Gulags, colonialism, or ancient Rome, not with “yourself”. Still, for some reason, this counterintuitive assertion resonates with me in a way few statements ever have. This short article explains why, the more I reflect on it, the truer the statement appears to be. To comprehend this quote, it is essential to understand its two main parts: the implications of being a slave, and the effects of an idea on a person.

First, it is important to understand what slavery means. Anti-Slavery International defines slavery as the exploitation of an individual through deception, intimidation, or force, by others for personal or commercial gain. Even though this definition has some merits, it only captures the mechanisms through which humans enslave other humans, as seen in the colonial era and in modern textile industries. It omits other shapes and manifestations of slavery, and, more critically to these reflections, it fails to describe what it implies to be a slave.

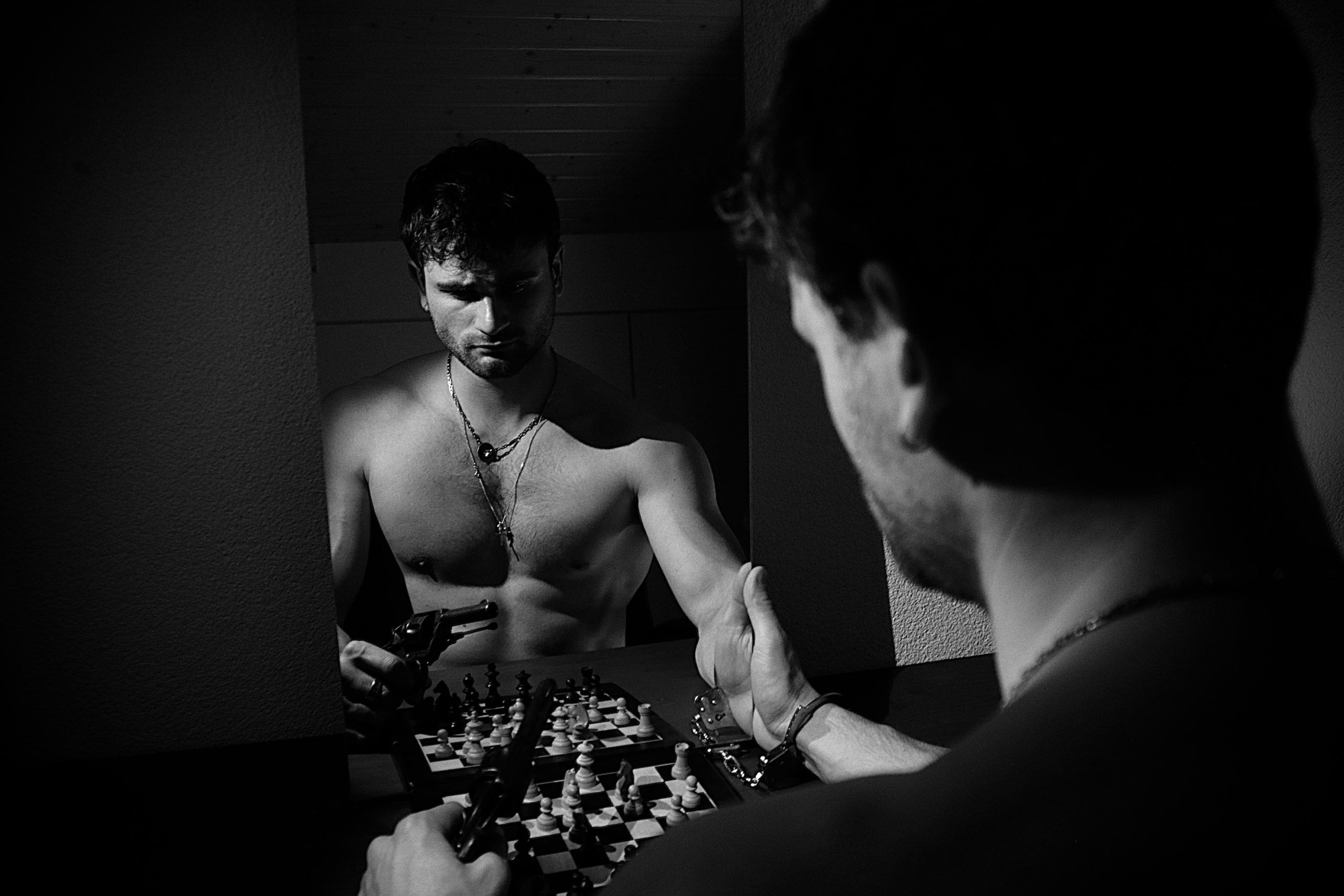

To grasp the latter, the idiom “enslaved to a substance” suggests a way forward. Indeed, this particular –however all too common– case shows that enslavement does not only describe a relation of power between men, but a state of being. Because of unpleasant, painful, and even sometimes deadly withdrawal effects, one is only able to feel better after taking the drug. Increasingly, one’s life is confined between the four walls of the needed daily dose. Aims, desires, and actions are chained to the potent thought of the next shot, and everything else fades into the background. In other words, free will is gradually eroded by the corrosive force of drugs, and step by step the soul loses its liberty to wander. As Pythagoras would say: “No man is free who cannot control himself”. This suggests that the state of enslavement is more than simply the deprivation of physical liberties, and the opioid chains might be just as strong as the iron ones.

Yet, even free from addictions and external restrictions, our ability to freely and independently think may still be constrained. In fact, some argue that men are shaped and conditioned by society, which systematically imposes culture, traditions, ideas upon its members. For example, in many cultures women are believed to be less talented in maths than boys. Instil in them that they are at least as good as boys, and they will perform just like them. Because men are social animals, peer and group pressure is a very effective –though soft and hardly noticeable– means to compel and nudge thoughts, regardless of the channel (e.g. family, face-to-face, or the internet). Hence, even societies that advocate tolerance and debate are already biasing their citizens into a particular direction. This raises the possibility that we might just think that we possess free will and free thinking, even though we are simple products of society. Which cuffs are the most difficult to break: the iron, the opioid, or the cultural ones?

If the state of enslavement implies the lack of physical as well as thinking liberties, another form of social enslavement may lie in how people see each other as individuals. As a matter of fact, who you have become depends in great part on your environment. What was your parents’ opinion of you? Did they think you were smart or sporty enough, or talented in any way? Did they support and love you the same as your siblings, or even at all? Did they have money? How did your teachers succeed in motivating you? Who are your friends? What books were you advised to read? All of this will make one confident or scared; hard-working or lazy; victorious or beaten. Opinions of others can be decisive in shaping an individual’s future. One is never completely free, neither physically nor in the mind. Instead, once again, without noticing it, big parts of individuals are defined by their social environment.

To a certain degree we are all the products of preexisting ideas, thoughts, words, ideologies, dreams, cries, beliefs, laughs, jokes, narratives, stories, grammar, gazes, looks, stances, and opinions. They have been bending the trajectory of individual lives and even History. Religion and spiritual beliefs are at the origin of pyramids and can be taken as the antidote to one’s sufferings. Narratives and ideologies stand at the heart of the Cold War and the concentration camps; they are also one of the main reasons why today Democrats and Republicans are less likely than ever to marry each other. Maybe, individuals are just marbles in an infinite cosmic pinball machine: slaves of our peers, drugs, and culture, without control over our own self.

Perhaps David Herbert Lawrence would not disagree with these reflections. Yet, it seems that the writer considers our own opinion of ourselves of even higher significance for our lives. In fact, some techniques can change outcomes and lives. For example, self-talk has been proven to improve or worsen performances of athletes and reduce or increase cognitive anxiety. Body language, or behaviour, also impacts one’s appearance towards others but even more importantly towards oneself. Because Men “talk themselves through movements”, it can induce a positive feedback loop. This is why Jordan Peterson recommendsstanding up straight with the shoulders back. Indeed, it is not difficult to imagine how one, by standing a bit straighter, might feel a little more confident. This confidence is projected outward and often elicits a positive response, which in turn reinforces the individual’s sense of self-worth. In tennis, it is said that you are your worst enemy. Indeed, if the competition is fierce on the tennis court, it is even more violent within the self. Two opposing narratives constantly fight for dominance: either you consider yourself as a winner or as a loser. On a personal level, I realized that if I wanted to be more confident on the tennis court, I had to grunt while hitting the ball. It helped me take more room, feel more important –at the centre of attention. Grunting brought me confidence because I felt at least equal to my opponent, if not superior. This assurance could perhaps lead me to win a point, thereby reinforcing this newly acquired confidence through a positive feedback loop. Still, I often ended up losing the match anyways (sigh!). Nevertheless, it helped me overcome myself. This struggle between two ideas extends beyond the frontiers of tennis and sports: it is existential. Self-doubt can surface at any moment, but especially, “when we are tired, we are attacked by ideas we conquered long ago”. Breaking free from these doubts is a hard and daily task (or duty?).

This may be the core of the issue at hand: we hesitate; we falter; we “do not know”. The voices of uncertainty and doubt easily stifle confidence because our abilities and limits have all too rarely been tested. Thus, we do not understand our capabilities, and we are unaware of all the possibilities awaiting us. And we do not dare, me the first. Hence, the competition inside our heads is often lost before it even really started. Self-perception and self-esteem will not only help one face a challenge, but they will also push one to engage it in the first place. In other words, whether one steps on a tennis court, applies for a job or a university directly depends on one’s self-worth. Do not start and you are sure to never finish. This is why winning the internal war at the beginning and then until the end is so crucial.

I believe this applies to many other domains of life. Without discounting the sufferings and horrors other forms of slavery, it seems to me that our most resilient chains are forged by our own self-perception. As Jean-Paul Sartre put it, “freedom is what you do with what has been done to you”. Yet, that we are first of all our own slaves would not be particularly negative, because it gives us the opportunity but also the responsibility to change our condition. As I understand David Herbert Lawrence’s quote, it is a message of hope. Indeed, if we are our own slaves, we are also our own masters. For me, breaking free is possible only through hard work on myself.